"Crusade Knights in Khevsureti" Grabs Tourist Attention Again

Georgia’s tourism industry has helped awaken a largely forgotten story about Khevsureti that would have the Khevsurs be the descendants of a band of lost Crusaders. This story has been dismissed as absurd by all serious scholars, but the growing popularity of the region has seen this unfortunate meme become a popular interest point for tourism guides and articles. Blogposts and message boards also discuss the “Lost Crusader” origin story as a hypothesis and theory, referencing “the experts and evidence” of ethnographic and historical sources.

Khevsur-related articles across the many language platforms of Wikipedia also treat the story as a credible theory. A 2014 article by Washington Post correspondent Bill Donahue states as fact that in Khevsureti one finds “nature-worshiping Christians descended from the last crusaders of Europe.”

Few online resources exist to counter these internet misrepresentations. Most notable are the efforts of Caucasus expert Alexander Bainbridge, whose website batsav.com offers a large amount of detailed and well-researched information about the peoples of the Caucasus, including personal communications with scholars and his own translations into English of much material.

In its most common version, the story describes of a band of knights who became detached from their Crusade and eventually found themselves in the Caucasus, where they settled and became the forefathers of the Khevsurs. This secret history was forgotten for nearly a millennium, so the story goes, until sharp-eyed Western travelers saw remnants of the Crusader heritage in their habits and dress.

The Russian serviceman Arnold Zisserman is most often quoted as the originator of the story and as an authoritative ethnographic source. Zisserman spent years with the Khevsurs and his accounts include much detail about the Khevsur manners of dress, personal conduct, details of swordplay, religious practices, and day-today activities. His articles about Khevsureti first appear in the Tbilisi Russian language newspaper Kavkaz in 1951.

In English, the most popular version of the story came from the celebrity adventurer Richard Halliburton, who published his account in a 1935 book called Seven League Boots in a chapter entitled “The Last of the Crusaders.” Told in highly-stylized rhetoric, Halliburton suggests the knights originally came from German-French region of Lorraine and cites for support the Khevsurs’ French-style armor and that their “otherwise incomprehensible speech still contains six or eight good German words.”

Although Zisserman claimed to have discovered this supposed connection, an older version appears in an account by a Frenchman named Edouard Taitbout. Taibout says in his book Voyages en Circassie en 1818 that a “fairly common opinion” holds that escaped Crusaders had preached Christianity to the mountain people of the Caucasus, and explains that these signs appear in a Maltese cross worn by Khevsurs on their clothes and shields, and in the French names they still bear such as “Devilete, Guillot, etc.”

In a footnote, Taitbout cites reports this information was relayed to him by a personal acquaintance, a Monsieur Hauy: “Je dois ces renseignements à M. Hauy, major du Génie, qui est peut-être l'unique Européen qui a pénétré chez les Khévsours, où le hasard l'a conduit et où son titre de Français l'a fait admettre. [I owe this information to M. Hauy major du Génie, who may be the only European to have penetrated Khevsur society, where chance has led him, and where he was admitted on account of his being French.]”

The above examples represent only only a few of the references to a Khevsur-Crusader connection by visitors to Georgia before the formation Soviet Union. The widespread fascination with this meme by outsiders and its recent revival present an interesting case of how foreigners perceive and romanticize Georgia to the present day.

By Ryan Michael Sherman

Ryan Michael Sherman of Cornell University will discuss the history and scholarly treatment of the Crusader connection and its influence on February 20th at the Spring 2019 Work-in-Progress series at the CRRC office at 1 Ramaz Chkhikvadze Street, near Tbilisi State University. For more information visit the Works-in-Progress Facebook page.

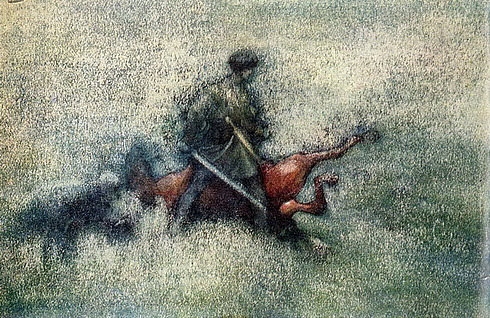

Image 1: Artist: Gigo Gabashvili, Drawing, “Warrior Khevsurs”

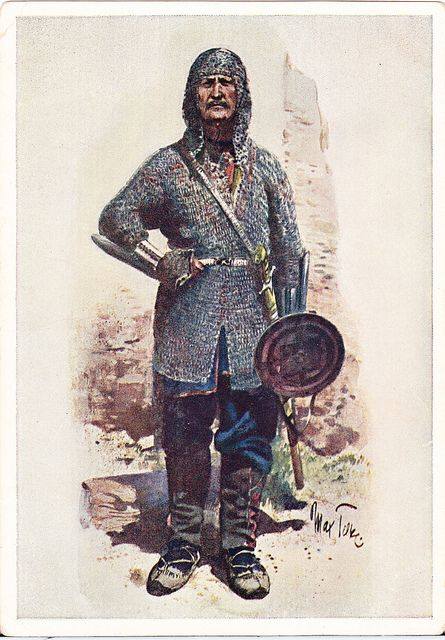

Image 2: Artist: Gigo Gabashvili, Painting, “Warrior Khevsur”

Image 3: Artist: Theodor Horschelt, Drawing, “Armed Khevsur”